Thor Hushovd won the World Championship Road Race in Australia this year with a powerful sprint finish to win from a 20-man group. In doing so he became the first Scandinavian to wear the Rainbow Jersey as champion of the road. He wasted no time in announcing that his major goal for 2011 would be to win Paris-Roubaix as reigning World Champion:

My goal is the classics next year, to try to win Roubaix in the rainbow jersey. That would be a dream for me. It’s an honor for any rider to wear the rainbow jersey for one year, and to win Roubaix would be even better.

Hushovd will be riding for the Garmin-Cervelo team next year. For the past two years, he has juggled classics leader and team sprinter duties with team mate Heinrich Haussler. However, Haussler has also made the move to the Garmin-Cervelo team. Thus, in 2011, Hushovd will now be sharing responsibilities with Haussler again, along with the equally ambitious Tyler Farrar.

Recently, Hushovd has announced that he is shelving his annual goal of winning the Tour de France Green Jersey in order to help his new team mate Farrar win it instead. Hushovd has won the Green Jersey twice before in 2005 and 2009 but could only finish third this year behind both Mark Cavendish and eventual winner Alessandro Petacchi. The Norwegian champion said this about helping Farrar in 2011:

We must go far back in time to find a flat stage where I beat Mark Cavendish. So, I’d rather help Farrar to beat him.

Hushovd’s not wrong. The last time he beat Cavendish in a sprint was Stage 3 of the 2009 Tour of Missouri, when Hushovd won the stage and Cavendish could only manage fifth. However, on that occasion there was a significant rise up until the one-kilometre-to-go banner, followed by a downhill sprint to the line. Hushovd also beat Cavendish in a flat sprint finish in the 2009 Tour of California, however on that occasion Cavendish could perhaps be excused as the conditions were very wet and he became involved in a tussle with a Rock Racing rider and his lead out train lost him. The last time where Hushovd truly beat Cavendish in a no-messing-head-to-head flat sprint finish was the 2007 Tour de France stage to Joigny which Hushovd won and Cavendish could only manage 10th. But this was when Cavendish was still only 22 and before his palmarés burgeoned into one of the most enviable in Tour history. Consequently, Hushovd’s decision to take a step back from confronting Cavendish seems like a wise one.

Thor Hushovd celebrating victory in the 2010 World Road Race

In one of the most talent rich teams ever assembled, Hushovd will be expecting absolute leadership in Paris-Roubaix in return for quashing his Tour de France ambitions. So, if we look back on past results, how likely is it that the new World Champion will win Paris-Roubaix?

Well despite the fact it hasn’t been done since 1981, the stats are actually very encouraging for Hushovd. Well, the stats I could find anyway. I managed to find full results lists for all the finishers in Paris-Roubaix dating back to 1938. However, these lists only included riders who finished and did not provide details of riders who may have started and subsequently abandoned. For instance, did Greg LeMond start and abandon the race in 1984? How about Fausto Coppi in 1954? Or Gerrie Knetemann in 1979? I’m not sure, but here’s a few nuggets of trivia based on what I did find.

Winning Paris-Roubaix as World Champion is a feat which has not been achieved for 30 years but has actually been done on five separate occasions. The most recent to do it was Bernard Hinault in 1981. Before him came Francesco Moser in 1978 and preceded by a young Eddy Merckx in 1968. Finally Rik van Looy managed it to do it twice in a row when he won back to back World Championships in 1960 and 1961, and followed it up with back to back Paris-Roubaix wins in 1961 and 1962.

Since 1939 there have only been 25 current World Champions who have ridden Paris-Roubaix. Taking into account the three year break in the race caused by World War II, that’s only 25 participations in 70 editions by the current World Champions. However, on only two of these 25 occasions did the World Champion finish outside the top 20, when André Darrigade finished a lowly 46th in 1960 and when Stan Ockers ended up in 21st place in 1956.

Perhaps the most remarkable stat to emerge was that of the 25 World Champions to ride the hell of the north, 15 of them actually finished on the podium – Five winners (all mentioned above), five runners up and five third place finishers. The curse of the rainbow jersey seems to be rather neutralised if you ride Paris-Roubaix.

In recent years, (i.e. the past 20), only three World Champions have taken part. Tom Boonen was the last to participate in 2006 when he finished 2nd behind his nemesis from this year, Fabian Cancellara. Although, it must be said, Boonen was only awarded 2nd after Leif Hoste, Peter van Petegem and Vladimir Gusev were all eliminated for ignoring a level crossing. Before Boonen, one of the more obscure World Champions, Romans Vainsteins, managed a third place in 2001 to round out a podium full of Domo-Farm Frites riders, the other two were eventual winner Servais Knaven and Johan Museeuw. The latter is the third rider in recent years to appear on the Paris-Roubaix podium wearing the Rainbow Jersey, he did so by finishing third in 1997 when he was beaten in the final sprint by Frédéric Guesdon and Jo Planckaert.

Tom Boonen and Johan Museeuw are both triple winners in Paris-Roubaix. Thor Hushovd has yet to taste victory in the Queen of Classics, but he has come close. In 2009, it appeared that Boonen, Filippo Pozzato and Hushovd would all reach the velodrome together and sprint it out for the win, but Hushovd crashed with just over 15km to go and soloed home in third place. Last year, he managed one better and came second, but seemed even further away from possible victory as Fabian Cancellara made a mockery of the rest of the competitors.

Hushovd dearly wants to win this race and he may not get a better opportunity. Tom Boonen has been out of sorts since his crash in the Tour of California in May and showed in this year’s race that he’s liable to a lapse in concentration. Boonen may also find himself sharing team leadership duties with cyclo-cross superstar Zdenek Stybar who fancies his chances at the cobbled classics next year, although the Czech rider is currently suffering from knee problems of his own. As for Fabian Cancellara, he has stated that he would love to win Liége-Bastogne-Liége next year. To get up the hills of the Ardennes, Cancellara will have to sacrifice some of his power on the flat, in addition to stretching his form peak further than any other riders with realistic ambitions of winning a cobbled classic (except perhaps Phillipe Gilbert).

While the curse of the Rainbow Jersey certainly has affected some riders over the years, Cadel Evans has proven that the Rainbow Jersey can also act as a catalyst to propel a rider’s career on to another level. If the curse decides to spare Hushovd from injury, he’s well poised to continue Evans’s example of greatly honouring the Rainbow Jersey by winning one of the biggest races in cycling.

Joaquim Rodriguez has finished the year as the leader of the UCI World Rankings. Naturally, one would assume that a world ranking is an indication of who the best rider in the world is. As an article in this month’s Cycle Sport magazine declares, “it doesn’t take a genius to work out that, no matter what the rankings say, Joaquim Rodriguez is not the best rider in the world“. The article goes on to state ‘the UCI World Ranking is fine if you want to find out who the most consistent rider in the world is. It’s not so good if you want to find the best“.

In my opinion, no matter how a season long competition is designed, what races are included or how the points are allocated, there will never be an objective indication of who the ‘best’ rider in the world is, this will always be a subjective opinion. If you appreciate the subtle intricacies and sheer power required to dominate time trials, then you would probably think Fabian Cancellara is the best rider in the world. If you enjoy watching bunch sprints, then Mark Cavendish is undoubtedly the best there is. If it’s nerveless exploits in descending mountains that whets your whistle, then perhaps you would consider Samuel Sanchez or Vincenzo Nibali the best of the best. Or what about a spectator who appreciates nothing more than watching a rider push himself to his physical limits in an enactment of pure sacrifice for the good of their team mates? Then perhaps Sylvester Szmyd or Chris Anker Sorensen should be considered the best in the world.

Joaquim Rodriguez - The world's best?

The winner of a season long competition will only ever indicate one thing: the winner of a season long competition. If the competition rules indicate that two second place finishes trumps a first place and consistency is king, then that’s what needs to be done to win that competition. The UCI World Rankings is essentially a points classification. Just as the points classification in the Tour de France does not necessarily reward the rider who wins the most stages, the title of World Number One does not necessarily reward the rider who won the most races throughout the season (that would be Andre Greipel). Both competitions reward consistency. Isn’t the Tour de France itself an exercise in consistency? A rider can dominate the Tour and win 20 stages out of 21 and still not walk away with the Yellow Jersey.

Riders have won the Tour de France in the past without winning stages (Alberto Contador, Greg LeMond, Gastone Nencini), riders have won the Green jersey at the Tour before without winning stages (Thor Hushovd, Erik Zabel, Sean Kelly) and riders have won season long competitions before without winning races (Maurizio Fondriest 1991 World Cup, Paolo Bettini 2004 World Cup). The difference between the UCI World Ranking and the aforementioned prizes is prestige. But what is prestige?

Prestige comes from a combination of history, attitude and money. Obviously any financial incentive for riders to win races cannot be ignored. Sean Kelly was famously nicknamed ‘sprint prime’ upon his arrival on the European cycling scene due to his focus on winning a race’s hot spot sprints and taking the wads of cash that came with them. Although money may be a motivation for a rider, the financial incentives for cycling as a sport are laughable in comparison to that of a sport like golf.

When the two sports’ top tier events are considered, admittedly, the difference isn’t massive. For instance the winner of the 2010 Tour de France (whoever it was) will receive €450,000. Whereas, the winner of the British Open golf tournament will walk away with €976,000. So the Golf prize money is more than double that of cycling, but still comparable. The real differences lie in the events that are not considered to be part of the top tier. Consider cycling’s Tour of Qatar and golf’s Qatar masters. Two events which have been around for about the same amount of time, host about the same amount of participants and take place over about the same number of days. The winning cyclist will get €9,000, whereas the winning golfer can pocket almost €300,000.

What is the point in a season long classification which compares Cavendish, Schleck and Cancellara?

As a sport which pushes the athletes to their physical limits, there is more than money to motivate professional cyclists. Consider two of cycling’s one day races; the Pro Tour level Grand Prix of Montreal and the not-even-considered-a-proper-classic Het Volk. If given a choice I know which race I would rather have on my palmarés. This is due to the history of the race, the list of past winners creates the prestige. Riders like Roger De Vlaeminck, Eddy Merckx, Jan Raas, Franco Ballerini and Phillipe Gilbert have all won Het Volk. To win this race is to elevate yourself into the same echelon as these riders. Winning the GP Montreal holds none of this prestige and importance, for the moment anyway. (Also, it must be said, that winning these historic races adds credence to your abilities as a rider, which in turn may mean a bigger pay packet when negotiating a new contract).

The prestige of a race also depends on the attitude of riders (and indeed media) toward a race. If Fabian Cancellara, Phillipe Gilbert, Cadel Evans and Mark Cavendish announced tomorrow that the Gorey 3 Day will be a major season goal for 2011, then suddenly the profile of the race is raised, the race would be covered by mainstream media and the race would become a sought after addition to a rider’s palmarés.

For the moment there is no prestige associated with topping the UCI World Rankings, it is seen as incidental to the racing season, not an integral part of it. But for a competition which compares apples with oranges it will always be incidental. I completely understand why Andy Schleck could never muster the motivation to want to best Mark Cavendish. It’s like asking who was the greater footballer, Roy Keane, Eric Cantona or Peter Schmeichel? Which brings me around to an old Irish Peloton post which suggested that the current season long rankings be divided into two. One for stage races and one for single day races. Perhaps then, riders may see the competitions as goals for the season rather than a by-product. Competitions, which of course would reward consistency, leaving the matter of who the best rider in the world is, up to debate, which is as it should be.

Today’s Stage 2 of the Tour de France was unorthodox to say the least. Again, as they did yesterday, crashes animated the stage. Race favourites Wiggins, Contador, Kreuziger, Armstrong, both Schlecks, Basso, and Vande Velde all fell victim to the slippy roads in the wet conditions. By far the worst affected G.C. favourite was Christian Vande Velde who finished 5:53 down on the yellow jersey group.

Both Schlecks also found themselves chasing back on after crashing twice within 200 metres. Luckily, their team mate Fabian Cancellara was wearing the yellow jersey. As the acting patron of the peloton he forced the front of the race practically to a stand still so that the fallen could catch back up. This well intentioned act from Cancellara resulted in him relinquishing his hold on the yellow jersey to Sylvain Chavanel who was busy up the road soloing home for the stage win. A particularly selfless act given the circumstances, as Cancellara’s ultimate goal for this year’s Tour was to wear the Maillot Jaune as the race rides over the cobbles on Stage 3. My question is whether Cancellara had the authority to enforce this decision on (what remained of) the peloton.

This type of incident occurred in the Tour before in 2003 when Lance Armstrong hooked his handlebar’s on a musette bag held by a spectator and came crashing down. His main rival Jan Ullrich went up the road, but between the German and Tyler Hamilton the front of the race slowed down until the Texan caught back up. Hamilton said at the time:

It’s an unwritten rule that if the Maillot Jaune crashes, you give him a chance to get back.

However, on that day it was the fallen’s rivals who made the decision to wait. Cancellara, although clad in yellow is nevertheless, a team mate of the Schlecks. Surely the decision to wait for them should have been made by a rival of the Schlecks and not from a team mate with a vested interest.

There have been some reports that there was some sort of oil spill on thed escent which caused most of the crash related mayhem. If this is the case, then some of today’s behaviour is somewhat excusable. However, if the crashes were merely caused by the wet conditions then it is simply a matter of poor bike handling skills or bad luck. In which case I completely disagree with Cancellara’s move to orchestrate a truce in the peloton until the Schleck’s caught back on.

Any rider aspiring to win the Tour de France needs to have a certain set of skills. Descending in wet conditions should be part of this skill set along with the more heralded skills of climbing and time trialling. If a rider slips and falls himself then it is his own mistake and other riders should be allowed to capitalise. If a rider falls because a crash has occurred in front of him and he is brought down as a result, then he is still not entirely blameless. Perhaps he chose the wrong wheel to follow and he should have chosen a more trustworthy descender to follow, or perhaps he should have positioned himself further up in the group in order to limit the potential for getting caught behind a crash.

Robbie Hunter said after today’s stage:

In the northern classics most of the bunch are used to riding on these roads. Most of the Tour peloton never ever do the classics.

If he’s referring to the Ardennes classics then he is incorrect, most of the Tour do ride these races. If he’s referring to the traditionally wetter muckier more treacherous variety of classics that take place a couple of weeks earlier then he is correct. A lot of the Tour peloton don’t ride this races. But they should. Everybody has known the route of this Tour since last year. Riders racing schedules should have been organised accordingly. Why is it then that Lance Armstrong is the only rider who rode one of these races this year. The rider’s who don’t usually ride in these conditions should have taken the opportunity to familiarise themselves with it earlier in the year.

As for Cancellara’s decision (in conjunction with the race organisers) to neutralise the sprint finish, I’m sure I’m not the only one that has a huge problem with this. Again, the riders all knew the route, and it’s Northern Europe after all, rain can’t be ruled out on any day of the year. Surely if the riders or directeur sportifs had a problem with the route or particular road furniture then they could have aired these grievances months ago. Apart from fans finding the stage end disgruntling, I’m sure there’s a team manager or two who aren’t too happy. Take Quick Step for example. Instead of bloggers and journalists writing about Chavanel and Pineau (myself being no exception) holding all three of the Tours major jersey between them, as well as taking the stage win, we’re all discussing Cancellara and Saxo Bank. Thus, limiting the exposure that the Quick Step team deserve and the Quick Step brand has invested in.

But the biggest loser of the day is probably Thor Hushovd. The race organisers decided that everyone except the stage winner Chavanel would not be awarded green jersey points. Hushovd managed to avoid the crashes and stay in the front bunch all day. His main green jersey rival Mark Cavendish didn’t crash, he was simply dropped. But due to circumstances beyond Hushovd’s control he was unable to capitalise on his rivals lack of climbing ability, which he should have been allowed to do. As his team mate Brett Lancaster said this evening:

Team worked hard today for Thor to get some points for the green jersey. It was all for nothing in the end because some riders crashed.

He’s one of my favourite riders in the peloton but Cancellara has a lot of questions to answer as there are many people losing out because of his actions today.

Milan San Remo,Tour of Flanders,World Championships

The classics season is in full swing and will continue this weekend with the 94th edition of the Tour of Flanders. The winner of the last two editions Stijn Devolder will be in with a chance of winning for the third year in a row, something which has only once before been achieved, by Italian Fiorenzo Magni almost 60 years ago. However Devolder’s Quick Step team mate Tom Boonen will also be looking to win his third edition of the race having won before in 2005 and 2006. Boonen is undoubtedly the leader of the Quick Step team at the classics, but ironically, it is Boonen’s status as leader that has allowed Devolder to win the Tour of Flanders for the last two years. In virtually identical races, 2008 and 2009 saw Devolder attack from about 20km out and solo home while other pre-race favourites were busy marking Boonen. Had Devolder been riding for any other team, Boonen’s Quick Step team mates would have chased down any breaks in an attempt to set Boonen up for his own race winning attack, therefore denying Devolder a victory.

However a third consecutive victory for Devolder is looking highly unlikely having shown appalling form throughout the season so far. Even his directeur sportif has been bemoaning his poor results this year. To illustrate, he has had no top 30 finishes at all this year and his best result in a cobbled race has been 40th in the E3 Prijs Vlaanderen last weekend. To put this into perspective, in the run up to the Tour of Flanders in 2009 he had racked up three top 10 places in the E3 Prijs, Dwars Door Vlaanderen and the time trial stage of the Three Days of De Panne. Further back in 2008, he had placed in the top 10 in two cobbled races and had also won the overall at the Volta ao Algarve. Devolder has said that he is still focused on completing his hat-trick of titles but it’s safe to say his form is dreadfully short of where it has been for the past two years.

But that’s not to say that Boonen won’t again be denied this year by a team mate. Sylvain Chavanel is also in a position to take advantage of Boonen’s status as race favourite and would be more than capable of ‘doing a Devolder’ and soloing home for a win. Chavanel has been solid if unspectacular so far this season. He has taken 20th place (ish) at Het Niuwsblad, Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne, Milan San Remo, Gent-Wevelgem and most stages of Paris-Nice. If a Quick Step rider other than Boonen is going to win this hilly cobbled classic the most likely rider will be Chavanel and not Devolder. But having not won the Tour of Flanders since 2006, Boonen will be hungry to reclaim the prize which he has been denied the last few years. If he does win this coming Sunday, he will become only the second man after Johan Museeuw to have won three editions each of the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix.

Another man who recently joined the club of riders to have won three editions of a monument classic is Oscar Freire. Having had a barren year in 2009 with only 2 victories to his name, his career seemed to be fizzling out. But having kept himself protected and largely anonymous until the peloton got over the Poggio, he stormed to the front on the finishing straight to take Milan San Remo for the third time in his career. Although Freire would not be considered a favourite for the Tour of Flanders he has a string of top 30 finishes to his name. But he he has stated that this year he won’t be riding the Ronde and that he wants to concentrate all his efforts on winning the Amstel Gold Race where he has previously finished 5th and clearly would like to add to his palamarés. A race which the Spaniard has won previously is the World Road Race Championship, on three occasions. To look over the previous winners of the six major one day races (5 Monuments + Worlds), Freire has joined Girardengo, Binda, Coppi, De Vlaeminck, Merckx and Museeuw as being the only men to be triple winners of two of those races.

In a World Championship the road race takes place on a different course every year. The course has a huge role to play in who are the favourites and what may constitute a race winning move on the day. Conversely, the monument classics are run on (almost) identical courses every year. This leads to the same riders being marked at the same crucial points throughout the race year after year. Thus, every year that a rider proves he can win one of these races, trying to repeat that victory the following year becomes increasingly more difficult as riders are then uber-aware of what a previous winner is capable of. This is what makes Devolder’s Tour of Flanders victory last year so remarkable. He had proven in 2008 that he had what it took to attack before the finish and solo home, and yet last year he was allowed follow the exact same route to victory.

Milan San Remo invariably boils down to who is the strongest sprinter on the day who can make it over the Poggio with the front group. Paris-Roubaix is often won by the strongest rider who has a bit of luck on his side. Last year Tom Boonen won solo without even having to formulate a race winning attack. The Belgian champion just powered home while everyone around him fell over. But the Tour of Flanders is a different monster with much more subtle tactics at play. A race winning break can be formed at a plethora of locations. There are six climbs in the last 50km of the race, each one providing ample opportunity to make a race winning move.

Another rider who wants to win the Tour of Flanders is Fabian Cancellara. Continuing the theme of triple victories, the Swiss power demon will be aiming to win his third different monument classic having previously won Paris-Roubaix in 2006 and Milan San Remo in 2008. He has stated that Flanders is a major career goal for him. Looking back on his career so far, having won three World Time Trial titles, worn the yellow jersey in three separate Tours de France, won the Olympic Time Trial title, won 7 Grand Tour stages, won his home stage race the Tour de Suisse and having won the aforementioned monument classics, it seems that what Spartacus wants Spartacus gets. However one race missing from his palmarés thus far is the World Road Race title. At Mendrisio last year he was clearly the strongest rider in the race but he suffered from over confidence and was defeated on the day by the more astute racing of Cadel Evans. Cancellara will have to be more tactically in tune if he is to be successful at the Ronde next Sunday. But, like Boonen, Cancellara also has a team mate who can steel away while his leader is being marked in the bunch by other race favourites. Matti Breschel has already won a cobbled semi-classic this year at the Dwars Door Vlaanderen and came 6th at the Tour of Flanders last year after Cancellara’s chances on the day were scuppered by a broken chain. The Danish champion may benefit from Cancellara’s intentions to go for victory this year.

Other contenders who should also be vying for victory on Sunday are Phillipe Gilbert, Filippo Pozzato, Juan Antonio Flecha, Alessandro Ballan, Thor Hushovd and Nick Nuyens. But each of these favourites also has a team mate who is also capable of challenging for victory, respectively they are, Leif Hoste (and Greg van Avermaet), Sergei Ivanov, Edvald Boasson Hagen, George Hincapie (and Marcus Burghardt), Roger Hammond and Lars Boom. Of all of these race contenders, each of them, except the youngsters Boom and Boassan Hagen and surprisingly the pair from Cervélo, have finished in the top 10 at the Tour of Flanders. Unfortunately last year’s runner up Heinrich Haussler will not be taking part due to a knee injury. Boonen once more is the out and out favourite, he has the hunger and the experience required to win. But with the experience of winning comes the burden of scrutiny, which may well afford plenty of opportunities for lesser riders to make a break for victory in this fascinating cobbled classic.

Unfortunately there are no Irish riders taking part in the Tour of Flanders this year. The cobbles aren’t a speciality of Deignan, Martin or Roche and the An Post-Seán Kelly team won’t be on the start line. But riders like Ronan McLaughlin, Mark Cassidy and Connor McConvey have all been gaining experience with the An Post-Seán Kelly team in cobbled races such as the E3 Prijs Vlaanderen and the Dwars Door Vlaanderen. So perhaps it won’t be too long before Ireland has a contender for the cobbled races.

Tom Boonen is a cross between a sprinter and a strong cobbled classics rider. He’s a multiple winner of both major cobbled classics, Paris-Roubaix and the Tour of Flanders. He’s also won six stages of the Tour de France along with the green points jersey in the Tour and the rainbow jersey of World Champion. Add to that most of the other cobbled races, Gent-Wevelgem, Grote Scheldeprijs, Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne, E3 Prijs Vlaanderen and Dwars door Vlaanderen and he’s won most of the races that a rider with his abilities would be capable of winning.

Notable races that he could win but hasn’t are Milan San Remo, Het Volk and Paris-Tours, although he has finished on the podium in all three. He has now come out and said that he would consider targeting the World Time Trial Championships in Australia next year. Can Boonen really adapt to becoming a time trial specialist in one season and challenge Fabian Cancellara for the World Time Trial crown?

The fact is that Tom Boonen has only ever won one time trial in his professional career. That was a 5km prologue in the 2.3 category Ster Elektrotoer in 2004. He has racked up a few good placings in prologue time trials down through the years, but so have a lot of sprinters. The power output required for a very short prologue tends to suit the abilities of powerful sprinters. Boonen’s main sprint rivals Mark Cavendish, Thor Hushovd and Tyler Farrar have all won prologue time trials. It is a massive leap to go from being a sprinter who can churn out a good prologue to a full-blown time trial specialist who can challenge over distances of 40km or more.

Although it must be said that when there is a long time trial during a stage race, sprinters tend to treat these stages as a rest day. They will just go through the motions, not over exerting themselves, conserving energy for when the next bunch sprint comes along. Perhaps Tom Boonen has never really given 100% in a long time trial before. His best ever result in a full length time trial came this year in the Vuelta a Espana, where he finished 11th in a 30km test against the clock. Not exactly sensational, but certainly an improvement on his previous efforts.

Perhaps Tom Boonen has taken a look at his sprinting rivals, most of all the two young phenoms Cavendish and Farrar, and thought to himself that he might never win another Tour de France stage or green jersey ever again. He might feel that he needs to shift his focus from sprinting to time trialling in order to keep his focus throughout the racing season. The cobbled classics are all done and dusted by April, the only races Boonen is likely to win after this are stages in minor stage races, that may not be enough to feed the ego of Belgium’s greatest sports star.

Bradley Wiggins proved this year that changing one’s physique and specialty is entirely possible with training, diet and preparation. But is it possible for Tom Boonen to become a time trial specialist whilst maintaining his dominance on the cobbles? Fabian Cancellara is the living answer to that question. Cancellara is amongst the perennial challengers on the cobbles and has also dominated the World Time Trial Championships in recent years. He even won both the World Time Trial and Paris-Roubaix in the same year back in 2006, showing that specialising in both disciplines is quite feasible. The two riders are also quite similar physically, there’s only six months difference between them in terms of age, according to their official websites they both weigh 80kg however Boonen is slightly taller at 6′ 4″ compared to Cancellara at 6′ 1″.

The general consensus is that next year’s World Road Race Championship in Geelong is going to be one for the sprinters. I can’t help but wonder why Boonen isn’t channeling his efforts towards this rather than the time trial. How can he think he’ll be capable of beating Cancellara when the rest of the world’s time trial specialists, who’ve been focusing on time trials their entire careers, can’t even get close to him? I don’t think any amount of time in the wind tunnel over the winter is going to help Boonen reach this most lofty of goals, he should stick to what he knows, cobbles and sprints.

Seán Kelly was known as the man for all seasons because he was as competitive at Paris-Nice in March as he was at the Tour of Lombardy in October. He seemed to be at peak or near-peak form right throughout the year. While this is a reputation that has stayed with Kelly, he was by no means unique in this regard. In the eighties the modern idea of preparing for a season and basing an entire training regime around one or two races was quite alien. Plenty of riders were highly competitive right throughout the season. What is actually more impressive about ‘King Kelly’ was his ability to challenge in such a wide variety of races.

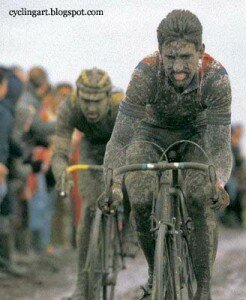

A mudcaked Sean Kelly in Paris Roubaix. Just one of the variety of races that Kelly was capable of winning.

There is no other rider (besides Eddy Merckx obviously) who can claim to have won completely different prizes such as a Grand Tour, the Green Jersey in the Tour de France, Milan San Remo, Paris-Roubaix and the Tour of Lombardy. Kelly was in fact the last rider in the peloton who could honestly claim to be competitive in all of cycling’s monument classics. He won Milan San Remo, Paris-Roubaix, Liége-Bastogne-Liége and the Tour of Lombardy all more than once. Although he was never victorious in the Tour of Flanders he did finish second an agonizing three times. In total he won 9 monument classics, he was 27 years old before he won his first and he took his last at Milan San Remo in 1992 at the ripe age of 35.

It takes a very special rider to be able to challenge in all of the monument classics. Milan San Remo is historically a sprinter’s race (it must be if Cipollini was able to win it) and more often than not does end up in a bunch gallop. However, there’s also room here for rider’s who are capable of riding away from the peloton with 1 or 2 kilometres to go. Then there’s the two cobbled classics, Paris – Roubaix and the Tour of Flanders. In an interview with Shane Stokes a couple of years back, Kelly himself described the kind of rider needed to win these races: “these are the ones for the strong guys, the big roulers with a little bit of extra weight. The sort of guys who can’t get up the big climbs but who can really power along on the cobbles”. Although Paris-Roubaix is pretty much pan flat and Flanders is somewhat hilly, it takes the same type of rider to win both. Proven by the fact that Tom Boonen and Johan Museeuw have won these races 11 times between them but neither have one any of the other monuments. Finally then it’s the hilly races of Liége-Bastogne-Liége and the Tour of Lombardy which Kelly has said “it is more a question of a rider who is an all-rounder. In other words, the guy who can do well in Paris-Nice, who can do well in Pays Basques and those sort of races.”

Of the five monument classics there seems to be three distinct categories of race to be won, sprints, cobbles and hills. So who, since Kelly, has even come close to challenging in all three categories. There was Andrea Tafi and Andrea Tchmil in the mid-nineties. Tafi won one edition each of Flanders, Roubaix and Lombardy but never featured in Milan San Remo. Tchmil was somewhat the opposite in that he too also won a Tour of Flanders and a Paris-Roubaix but never featured in either of the hilly races, instead taking victory in Milan San Remo. Then there’s Michele Bartoli who won Flanders, L-B-L twice and Lombardy twice but, like Tafi, never won Milan San Remo. Finally, in more recent years there’s been Paolo Bettini who comes closest to ticking all three boxes. He won four editions of the two hilly races, a Milan San Remo and once finished 7th in the Tour of Flanders.

Paolo Bettini winning Milan San Remo wearing the leader's jersey of the now defunct World Cup.

So no rider since Kelly has won a monument classic in all three of the categories. Is there anyone in the current peloton capable of doing so? Currently racing, there are only two riders who’ve won more than one of the five monuments. Tom Boonen (ToF ’05, ’06 and P-R ’05, ’08, ’09) and Fabian Cancellara (MSR ’08 and P-R ’06). Perhaps it’s the lack of a year long one-day racing competition like the old World Cup that has contributed to the demise of all round classics specialists. Or perhaps it’s the current trend in the peloton for riders to focus on very specific races which makes it very difficult for one man to be competitive in all of them.

But there must be somebody out there who’s willing to break the mold. Edvald Boassan Hagen has been tipped for greatness. The only classic he’s won so far has been Ghent-Wevelgem, but he’s only 23 and he’s already won one-day races, time trials and week long stage races. Then there’s Cancellara himself who’s already got two boxes ticked with Milan San Remo and Paris-Roubaix but how about the hilly classics? Well he proved this year that he’s capable of going uphill with the best of them at the Tour de Suisse and at the recent World Championships it must have been hard for him to stomach how a rider in such form and looking that strong failed to take the victory (the lack of a team didn’t help). The abilities needed to win on that course in Mendrisio would be comparable to those required for either Liége-Bastogne-Liége or the Tour of Lombardy. He’s also stated his desire to win all five before he retires.

What of the other men who showed their strength at the early season classics this year, Heinrich Haussler and Fillipo Pozzato? Pozzato has won an edition of Milan San Remo, finished 2nd in Paris-Roubaix and 5th in the Tour of Flanders but has never applied himself to the hilly races, his best result coming in Lombardy where he once took 19th. Haussler is a similar story, missing out on Milan San Remo by the slimmest of margins earlier this year, he also took 2nd in Flanders this year and finished 7th in Paris-Roubaix. But he has never even attempted the other two races. Although he did take a medium mountain stage victory in the Tour this year, but that was when the peloton had thrown their toys out of the pram due to the race radio ban so maybe we shouldn’t read too much into this for his hilly credentials.

Finally, the man in the current peloton who by far has the most potential to win all five of cycling’s monuments…Phillipe Gilbert. He’s just won his first monument by taking the Tour of Lombardy two weeks ago and that surely will be the first of many. He’s finished 3rd in both Milan San Remo and the Tour of Flanders and has also finished 4th in Liége-Bastogne-Liége. He meets all the criteria for potential and has started to come good now on filling that potential. He’s still only 27 years old and the way in which he dominated the late season races, taking 4 wins in a row over an 8-day period, was utterly impressive. Seán Kelly won the Tour of Lombardy in 1983, his first monument classic, at the age of 27. Phillipe Gilbert has just done exactly the same. It takes a special rider to juggle all of the attributes needed to win all of the major one day races but Gilbert is doing a better job than most.