October 21, 2013 by Irish Peloton

The Truth and Complication Commission

The new UCI President Brian Cookson made a number of campaign promises as part of his election manifesto. One of these was the establishment of some sort of process to determine the truth about the doping problem within the sport, primarily so that a figurative line could be drawn demarcating the ushering in of a new era.

Presumably this would result in a deluge of doping related scandal with no repercussions for those participating. After this process, punishments for doping offenders would be more severe and the drip feeding of doping stories which has been occurring since the Festina affair rocked cycling in 1998 would be at an end.

But just how realistic a proposition is this for the sport of cycling? Why would any rider or directeur sportif, who has gotten away without being caught so far, suddenly ‘fess up? Everything we know about the sport of cycling and its code of silence suggests this is not going to be straight forward.

Bradley Wiggins’s first autobiography – In Pursuit of Glory

One of the major windows we are able to look through into the mindset of current and former riders, and what they are willing to openly discuss, is an autobiography. While not every rider has been in embroiled in doping scandal personally, they have all been affected to some degree by the misbehavior of others.

Bradley Wiggins is a prime example of this type of laterally affected rider. In the first of his (many) autobiographies ‘In Pursuit of Glory’, Wiggins address the topic of doping:

“I’m interested and I’m not. This is my sport and my profession and I want it to be clean, and in that respect there is an urgent need to understand why these people need to cheat and how it works. Some of them are guys I consider to be decent human beings who obviously, in some way, have a serious flaw in their make-up. That doesn’t necessarily make them bad people, just imperfect humans.

“At the same time I abhor what they do, their actions make my life as a cyclist infinitely more difficult, and I want absolutely no part of it. It’s a dilemma. Sometimes I care deeply about it and them, and sometimes I go into denial and can’t be bothered to even acknowledge it goes on – I just want to get on with my life and make sure these cheating maggots don’t impinge on my life one jot.”

Wiggins writes in some detail in this book about Floyd Landis testing positive at the 2006 Tour de France and how it affected his own life afterward. He also goes on to discuss, quite angrily, how his Cofidis team-mate Christian Moreni and Alexander Vinokourov were busted at the 2007 Tour. Whether we agree with Wiggins’s views or not, he offered them up in a book when there was no requirement to do so. He was not directly involved in any of these doping incidents and yet he chose to let us know how he felt at the time.

My Time – The most recent Wiggins autobiography

The first edition of ‘In Pursuit of Glory’ was published in 2008, before Wiggins’s fourth place at the 2009 Tour which propelled him into the realm of ‘Tour de France contender’. By the time he wrote and released ‘My Time’, he had gone on to win the Tour and had sat through dozens of press conferences where, instead of being asked about the race that just happened, the topic of the day was often doping.

In ‘My Time’, the sense of anger is still prevalent, but it is no longer anger solely at the dopers, but by now it had also become anger at those asking about the doping:

“I knew that if I went well at the Tour these accusations were going to happen more and more. I was waiting for it. I had decided that when the question was asked I wasn’t going to give it the old ‘I can sleep at night with a clear conscience’ and all that sort of crap…..I wanted to nip the accusations in the bud straight away. When someone asked that question, I just went for it: I don’t see why I shouldn’t be allowed to do that. Even if we are athletes in a public position, we are also human beings….I don’t get angry in public very often…but there was a good reason for my anger.

“I can understand why I was asked about doping, given the recent history of the sport, but it still annoyed me. I’d assumed that people would look back into my personal record; there is plenty I’ve said in the past that should make it clear where I stand”.

“On a personal level, the way I look at it now is that, as the yellow jersey, the pressure is on me to answer all the questions about doping – even though I’ve never doped. I was asked the questions in the Tour and I gave the answers I did. I don’t like talking about doping, but during the Tour, as the race leader, I had no choice.”

The impression throughout his later book ‘My Time’ is of a Wiggins who is much less interested in giving opinions on doping for the sake of opinions, something he did more of in ‘In Pursuit of Glory’. Despite this however, Wiggins still devoted an entire chapter to doping called ‘In the Firing Line’ along with other spurious mentions throughout the book.

Hunger by Sean Kelly

But compare Wiggins to Sean Kelly and Wiggins comes up sounding like a veritable motormouth. Kelly has his own recently published book called ‘Hunger’. The Irishman offers his side of the story of the doping incidents he was involved with himself, but no more. Kelly was interviewed about his book on the Second Captains podcast recently, where he said:

“The [autobiography] is about myself, it’s not really about doping. If you go into every situation you could take over half the book with that… I don’t know if people are too interested in going into a book about Sean Kelly talking about doping for 50% of the book. They wouldn’t be interested in that at all….I went through the problems I had in my career and I feel I covered all that. That was all I needed to do.”

Kelly explains to us what happened when he tested positive at the 1984 Paris-Brussels. It is the same explanation that we were given in David Walsh’s book about Kelly published in 1986. And it is the same explanation which is so completely different from Willy Voet’s recounting of the same incident in his book ‘Breaking the Chain’. But Kelly doesn’t mention Voet and he’s happy to tell us that there was something iffy about the testing procedure and leave it at that.

Domestique by Charly Wegelius

Kelly doesn’t give us information or opinions on other doping cases or other dopers. He doesn’t tell us he’s not going to write about this stuff, he just doesn’t write about it. However it’s not uncommon now for an autobiography of a cyclist to actually tell us exactly what we won’t be reading in the book we’re about to read. The recently retired Charly Wegelius is one such example. The following is contained in the first few pages of his new book ‘Domestique’:

“the book – like my career – does not contain any exciting doping stories, nor does it attempt to. It’s not to say that a fair amount of doping wasn’t going on around me, I’m sure. Anyone who feels the need can go and look up the names of the people I rode for and with and find numerous doping violations against their names. I am not trying to deny that. I have, however, chosen not to focus on those facts.

“I have remained true to my vision of the book. This book, the one that I wanted to write, is focused on something else: an entire cycling career. Yes, doping makes an appearance or two, there is no way it couldn’t, but I would like to feel that its small appearances in this book reflect just how minor a part it really played in my life as a cyclist. There was simply much more to be getting on with, so much more to the job and so much other stuff for me to be worrying about.”

As Wegelius informs us, the list of those he rode for, and with, who were sanctioned for doping offences is indeed numerous. Gianni Bugno, Pavel Tonkov, Franco Ballerini, Stefano Garzelli, Stefano Zanini, Danilo Di Luca and Thomas Dekker are just a few of the big name riders who got themselves into trouble while Wegelius was a team-mate.

Wegelius had his own troubles to discuss as he goes through in detail the problems he faced with having a naturally high haematocrit. At the time, the UCI imposed an allowed haematocrit level of 50%. Wegelius’s life became difficult when he breached this limit before the Tour of Lombardy in 2003. It was an incident which almost cost Wegelius his career and almost bankrupted him. An entire chapter entitled ‘Unfit to Race’ is devoted to this affair but we hear nothing of Wegelius’s shady ex-team-mates. But should we really expect to? We’re told about the incident which directly affected Wegelius himself, and as he himself informs us, there’s simply much more to be getting on with.

It’s all about the bike by Sean Yates

Another recently released autobiography also contains a disclaimer similar, but much more all encompassing, to that of Wegelius. ‘It’s all about the bike’ by Sean Yates tells us the following in the opening pages:

“If you want to read about who stuck what needle in whose arm at what race in the back of whose car in 1983 or whenever, then I’m afraid you’re reading the wrong book. This is a book about cycling, not about drugs. There are acres of information about that sort of thing on the internet and in other books, you don’t need it from me and I’m not interested in talking about it. I want to talk about cycling.”

Yates gives us a similar stance to that of Kelly where there’s far too much racing to discuss to get distracted with the mundane topic of doping. But where Kelly provides us with the bare minimum, Yates provides us with nothing at all.

Yates won the Tour of Belgium in 1989, the first stage race victory of his professional career. He recalls this big win over the course of two pages where he describes the nip and tuck racing where he eventually beat the Dutch rider Frans Maassen by the slenderest of margins.

What Yates doesn’t tell us is that the urine sample he provided after winning both stages of a split-stage day, tested positive for nortestosterone, an anabolic steroid. This is a doping positive which is listed on his Wikipedia page and archived on the excellent resource for all things doping Dopeology.org. But the references to source material from both websites are to text versions of foreign newspapers (one French, one Belgian). Perhaps Yates reasoned that these links were not sufficient to warrant people realising that this incident actually happened. Perhaps he reasoned that if he didn’t mention it in his official recount of his own career that the incident would be forgotten.

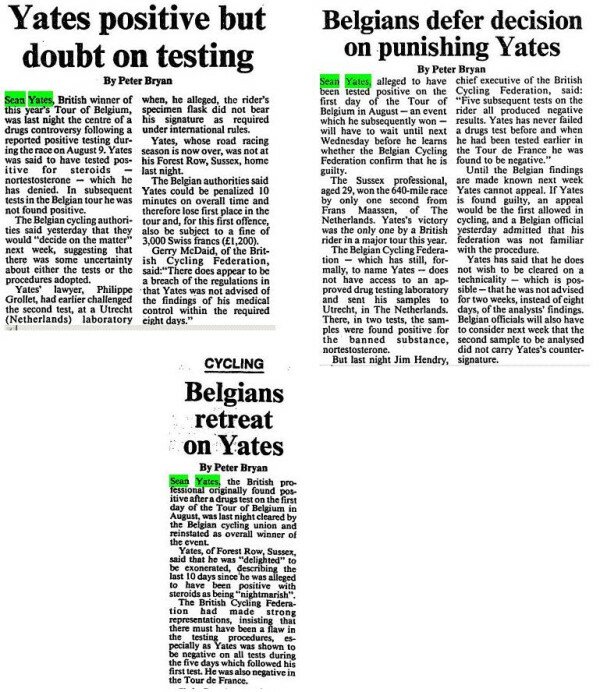

Unfortunately for Yates, there’s more to the internet than Wikipedia. The following are a collection of articles written in The Times by Peter Bryan which establish what actually occurred with Yates’s positive test at the 1989 Tour of Belgium.

At the time, Yates described the incident as ‘nightmarish’ and ultimately, he was adjudged to have done nothing wrong and he was not sanctioned. It seems strange then that Yates would choose to completely ignore this significant event in his cycling career considering he was not at fault. In the interest of transparency, the bedrock on which his most recent employers Team Sky base themselves, surely Yates would have been better off giving his side of this story.

But then again, why would he mention it? No point getting into something that’s going to drag up unwanted questions and avoidable bother. No, better off just ignoring and staying silent on the issue, after all, nobody was making him write this book.

World champion Lance Armstrong and Sean Yates in the 1994 Tour de France

Upon examination of the autobiographies of various cyclists it becomes apparent quite quickly that some riders will talk a lot, some will talk a little and some, like Yates, won’t say anything at all. It’s hard to imagine any truth and reconciliation process concocted by the UCI being any different. Ultimately, the problem will be, how to you get riders to talk?

Creating incentives for riders to talk seems an impossible road to go down. What can the UCI offer them? Money? Kudos? If guys like Kelly and Yates wanted money and kudos to come clean with what they know (if indeed they know anything) then they would have been better served putting it in their books and making more money off of book sales. Besides, the UCI doesn’t even have enough money to adequately test current riders, it certainly doesn’t have enough money to be handing out wads to whistleblowers.

The other road to go down then would be one of sanctions rather than incentives, for those who dope after the line in the sand is drawn. For riders, it remains to be seen how enforceable such an approach would be. The UCI attempted an approach resembling this in the past. A year after the Operation Puerto case was blown wide open on the eve of the 2006 Tour de France, the UCI asked riders to sign a charter which stated:

“I swear to my team, my colleagues, the UCI, the cycling world and the public that I have not cheated, have not been involved in the Fuentes case or in any other doping case. I declare myself ready to give a DNA sample to the Spanish judicial system so that it can be compared to the blood bags taken in the Operación Puerto.”

There was also a stipulation included which stated that if a rider was to sign this charter and subsequently tested positive, the rider would be banned for two years and would also be fined an amount equal to a year’s salary.

Paolo Bettini – single handedly and easily undermined the UCI’s attempts to draw a line in the sand.

The world champion at the time was the Italian Paolo Bettini who was preparing to defend his rainbow jersey in Stuttgart. Bettini had refused to sign the charter with its current wording and as a result, the UCI attempted to prevent Bettini from taking part in the 2007 World Championships. But Bettini stood firm and ultimately, the UCI were forced to admit that their charter had no basis in law and they also could not prevent Bettini from taking part. To add insult to injury, Bettini won the race and was world champion for another year.

But it highlighted how difficult it is to force riders to sign up to something like this. Any agreement with which Cookson attempts to entice riders into spilling the beans will have many legal hurdles, presumably involving the legal systems in lots of different countries. For instance, some forms of doping are illegal in France but are not illegal in Britain. Will French riders be treated differently to British riders as part of this process?

The quest to find ample incentives or sanctions for current riders is problematic. It seems, the worst that the UCI can do is to ban a rider for life, if that is deemed allowable by WADA, something which is not allowable under current rules for a first offence. But the quest to find relevant incentives or sanctions for the non-rider members of teams is problematic on a whole other level.

The worst that the UCI could do to a directeur sportif or soigneur or coach, it would seem also, is to ban them for life from the sport. This, of course, means the person in question would lose their job. But this is happening already.

A French senate report released shortly after this years Tour de France contained information about riders who had failed a retroactive test for EPO at the 1998 Tour de France. There was also information on riders who had not failed the test for EPO, but who were deemed highly suspicious of having taken the performance enhancing drug.

As a result of this report, Laurent Jalabert lost his job as a pundit with France Télévisions and with RTL Radio commentating on the Tour de France. Similarly, a bemused Abraham Olano also was required to forfeit his job as the route designer of the

Laurent Jalabert – lost his job after an unofficial positive test from 15 years ago.

Vuelta a Espana as a result of his presence in the French senate report.

Additionally, Team Sky took it upon themselves to conduct internal inquiries about their current staff which led to Geert Leinders, Steven de Jongh and Bobby Julich all losing their jobs. Sean Yates also ended his involvement with the team after an internal investigation but we are assured the timing of his departure is a mere coincidence.

It’s possible to conclude that the co-operation of the non-cyclist members of a team, those who have purchased, smuggled, monitored and administered doping products, is actually more important than the co-operation of the riders themselves, who simply utilise the doping products. But when people like this are already losing their jobs when they are caught, the two most logical paths to tread are to cease their nefarious behaviour (if it’s still ongoing) and say nothing or to keep going with their nefarious behaviour and say nothing.

The incentive to ruin their own reputation when they’re gaining nothing in return isn’t going to cut it. Sure, they’re aiding in the process of ushering cycling into a new era, but without incentive or without sanctions that don’t already exist, a reconciliation process which involves team staff is dead before it even begins.

Cookson’s task is not an easy one. There is no guarantee that all relevant parties will co-operate with a truth commission. Conversely, there is almost certainly a guarantee that some relevant parties won’t co-operate with a truth commission. As we’ve seen from rider autobiographies, some of them just have no interest in discussing doping. Without total co-operation, it’s very easy for people to adopt an ‘I’m not talking if he’s not‘ policy. Far from being an easy one, it’s difficult to imagine how Cookson’s task is anything other than impossible one.

Vanilla_Thrilla - October 21, 2013 @ 11:58 pm

A very good read, but may I request that you stop calling it Truth & Reconciliation and call it what it actually would be – an Amnesty.

Like most other amnesties, eg for illegal firearms, unpaid tax, etc, the only incentive to sign up is to avoid a punishment that one might otherwise face. And as with other amnesties, some people will take advantage of it, others will decide to carry on in the hope they wont get caught.

Would an amnesty in cycling get enough takers to be worthwhile? Who knows. On the negative side, the exposure to potential criminal charges in France and/or loss of legacy may skew the cost-benefit calculation for a large proportion of riders towards keeping quiet. On the positive side, the fall of Armstrong shows that no one is ‘too big to fail’. Also, if people no longer fear getting sued for fessin’ up, you could find it just takes a few riders to spill the beans on a number of others and what’s left of the facade of pro-cycling during the EPO era crumbles completely into dust.